The DC Office of Human Rights is proud to remember the contributions of generations of Black Americans, and highlight their lives and stories during Black History Month 2014. Throughout February, our office will share significant moments in the District's progress, and you will hear from our own staff about their experiences and how key figures inspired their lives and work. We will also encourage your participation through our social media platforms by presenting videos with meaningful questions about what it means to be Black in America today.

Historical Event of the Week

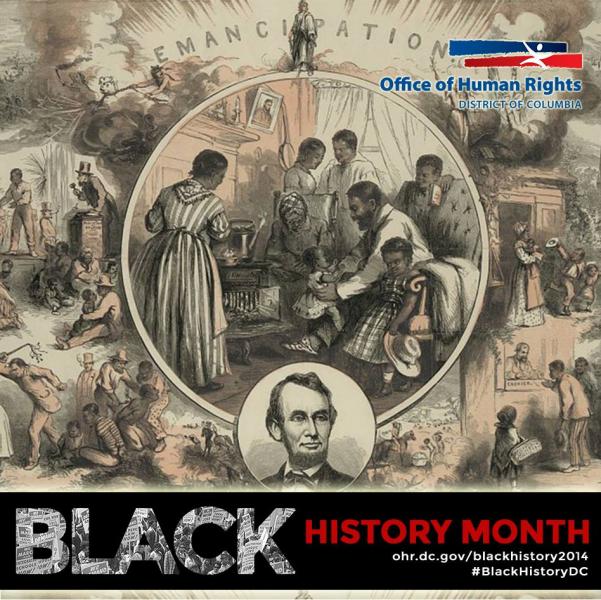

Week 3: Emancipation Day in the District

Week 3: Emancipation Day in the District

April 16, 1862 marks the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia. Over 3,000 enslaved persons were freed eight months before the Emancipation Proclamation liberated slaves in the South. The District also has the distinction of being the only part of the United States to have compensated slave owners for freeing enslaved persons they held.

The struggle to end slavery in the District was long and arduous. From the city’s beginning, various individuals and groups, with often diverse motives, signed anti-slavery petitions, wrote negative newspaper articles, and openly deplored the wide open practice of slavery and slave trading that occurred all over the city. Incidents such as Nat Turner’s 1831 rebellion in Virginia, and Snow Riot of 1835, the Pearl Affair and Riot in 1848, and the presence of the local Underground Railroad also highlighted the issue of slavery in the District.

As thousands of blacks flocked to the Nation’s capital seeking a haven from bondage during the early years of the Civil War, pressure increased on President Abraham Lincoln to take a bold step. With the help of Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, Lincoln got the bill through Congress. On April 16, 1862, he issued the emancipation decree for the District.

- Excerpt provided by emancipation.dc.gov.

Week 2: Mary McLeod Bethune Joins FDR Administration

Week 2: Mary McLeod Bethune Joins FDR Administration

The Black Cabinet was first known as the Federal Council of Negro Affairs, an informal group of African-American public policy advisors to United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt. It was supported by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. By mid-1935, there were 45 African Americans working in federal executive departments and New Deal agencies.

One of the most well-known members and only woman among the young was Ms. Mary Jane McLeod Bethune. "Ms. Bethune was a Republican who changed her party allegiance because of Franklin Roosevelt." Ms. Bethune was very closely tied to the community and believed she knew what the African Americans really wanted. She was looked upon very highly by other members of the cabinet, and the younger men called her "Ma Bethune." Ms. Bethune was a personal friend of Mrs. Roosevelt and, uniquely among the cabinet, had access to the White House. Their friendship began during a luncheon when Mrs. Roosevelt sat Ms. Bethune to the right of the president, considered the seat of honor. Franklin Roosevelt was so impressed by one of Bethune's speeches that he appointed her to the Division of Negro Affairs in the newly created National Youth Administration.

Bethune is still known today as "The First Lady of The Struggle” because of her commitment to bettering African Americans. Her house in Washington, D.C. in Logan Circle is preserved by the National Park Service as a National Historic Site, and a sculpture of her is located in Lincoln Park in Washington, D.C. in tribute to her great work.

- Largely excerpted from Wikipedia

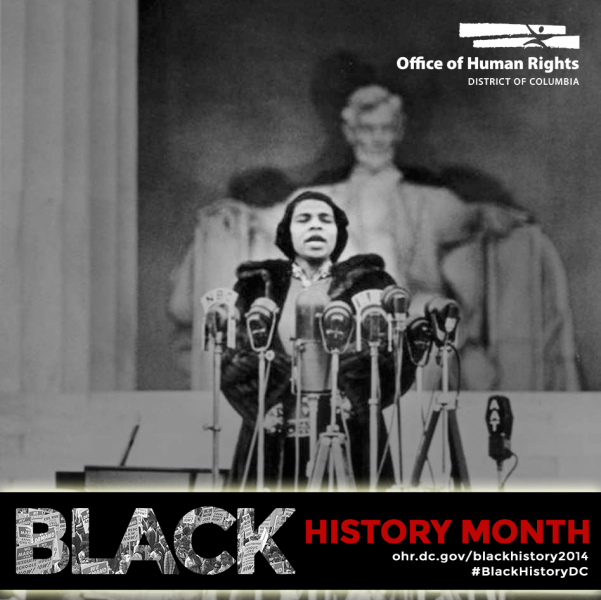

Week 1: Marian Anderson Sings at Lincoln Memorial

The year was 1939. At the time Washington, D.C. was still a segregated city and world renowned vocalist, Marian Anderson was denied the opportunity to perform to an integrated audience at Constitution Hall by the Daughters of the Revolution (DAR). In efforts to save the scheduled performance date request was sent to the District of Columbia Board of Education for use the auditorium of a white public high school. This request was also declined. In response, a co-founder of the NAACP and chair of the DC citywide Inter-Racial Committee, Charles Russell, convened a meeting the following day that formed the Marian Anderson Citizens Committee (MACC) comprised of several dozen organizations, church leaders and individual activists in the city. MACC elected Charles Houston as its chairman and on February 20, the group picketed the board of education, collected signatures on petitions, and planned a mass protest at the next board of education meeting.

As a result of the ensuing controversy, thousands of DAR members, including First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, resigned. In her letter to the DAR, Roosevelt wrote, "I am in complete disagreement with the attitude taken in refusing Constitution Hall to a great artist ... You had an opportunity to lead in an enlightened way and it seems to me that your organization has failed."

Many people criticized Eleanor Roosevelt's public silence about the similar decision by the District of Columbia Board of Education, while the District was under the control of committees of a Democratic Congress, to first deny, and then place race-based restrictions on, a proposed concert by Anderson.

President Roosevelt and Walter White, then-executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, as well as Anderson's manager, convinced the U.S. Secretary of the Interior to arrange an open air concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. The concert was performed on Easter Sunday, April 9, 1939. Anderson began the performance with a dignified and stirring rendition of "My Country, 'Tis of Thee". The event attracted a crowd of more than 75,000 of all colors and was a sensation with a national radio audience of millions.

Quote Bridge Video of the Week

Week 3: The Legacy of Fannie Lou Hamer

OHR's Jewell reads the words of Fannie Lou Hamer and poses a question to Judge Harris of the Commission on Human Rights. Watch on YouTube.

Week 2: The Legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr.

OHR's Aimee reads the words of Martin Luther King, Jr. and poses a question about progress on health care to OHR Investigations Director Rahsaan. Watch on YouTube.

Week 1: The Legacy of Rosa Parks

OHR's Sandy reads the words of Rosa Parks and poses a question about her legacy, to which OHR Policy & Communications Officer Stephanie. Watch on YouTube.